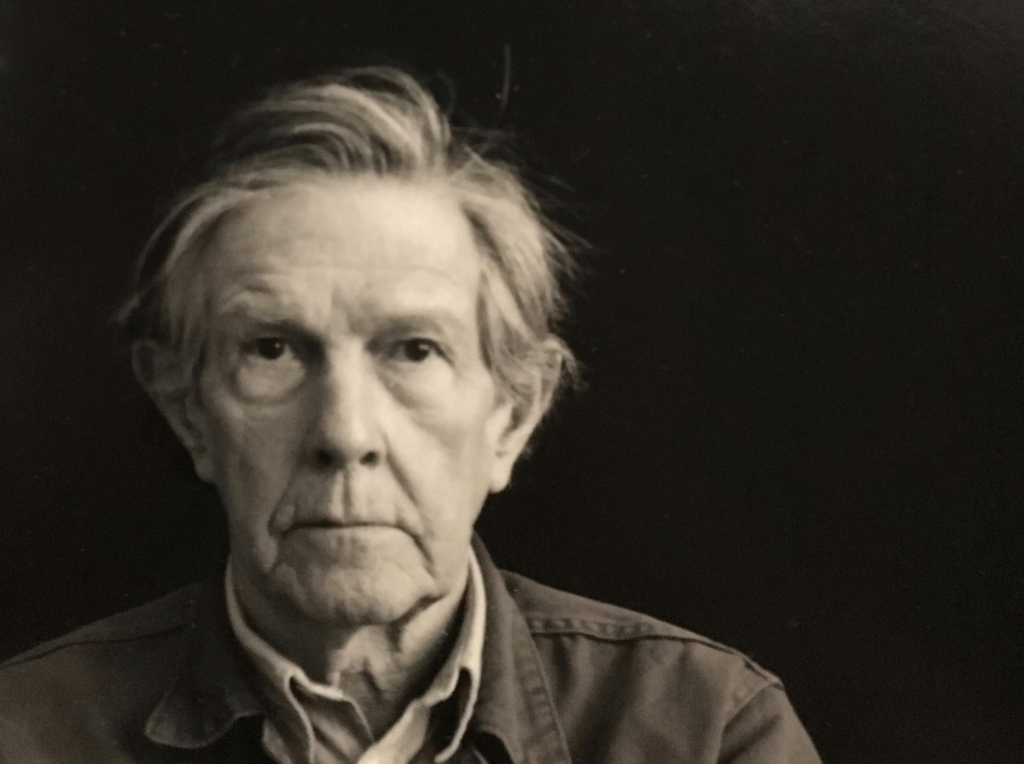

John Cage

in conversation with Thomas Moore and Laura Fletcher

Laura Fletcher and I spoke with John Cage on November 18, 1982, in Washington, D.C.

Thomas Moore: In reference to last night’s performance at the Terrace Theater, could you tell us something about the structure of Branches?

John Cage: It’s improvisation within a structure determined by chance operations, so that what each musician has is eight minutes divided by chance operations into smaller groups, not of seconds, but of minutes. So it would be, for example, four minutes, two minutes, one minute, one minute. Or it might be four minutes, four minutes; or it might be three minutes, two minutes, two minutes, one minute. Then there are ten instruments and what is an instrument can be determined by each performer. For instance, one spine could be one instrument, another spine another. Or the whole cactus could be an instrument, and there are ten of those, and the tenth one is the pod rattle, and must go in the last section of the eight minutes. Then between one eight-minute performance and another there is to be a silence, also determined by chance. I had thought of it, if it were to be played by a number of people, as it was the other evening — I had thought of it as being determined by each person independently of the other. But what the Nexus group did was to determine it for the whole group, and to play it in what you might call vertical harmony, rather than, as I had imagined it, contrapuntally, with each person independent of the other. I explained this to them that their understanding of the piece was different than mine, but my directions are actually always ambiguous, and I do that in order to leave the door open for a musician to make an original use of the material.

Laura Fletcher: We just performed Variations II, and that’s very ambiguous.

JC: Well, that, no, that’s almost impossible to understand! (laughs)

LF: We spoke with David Tudor when he was down here earlier, and his ideas were rather different than ours.

JC: Yes. I think it’s interesting to have — to make something like that, that each person has to understand for himself, don’t you think?

TM: I did see a performance of Variations II once in which the performer completely misinterpreted the score. Have you seen this sort of thing occur?

JC: Oh, I’m sure it does happen, yes. I think similar things happen even to explicit pieces, so I don’t think we have to worry. (laughs)

TM: Did you work with Nexus on Branches prior to the performance?

JC: No. No, I just let them do what they do. If they would ask me — because they probably would if we had a chance to talk — of what I thought of the performance and so forth, I would lead them away from continual activity in a sense of silence as activity. So that within one of the structures, say, four minutes, it’s not necessary to be continually making sound. You can fill that four minutes up by simply putting one sound halfway through the third minute. Instead of being a lawmaker I would like to have my work take on the character of stimulus or suggestion. I don’t mean that in terms of license, but in terms of poetry.

LF: Your comment regarding silence as activity is interesting in relation to our recent performance of Variations II, for which use used two piano interiors, marimba, and electric guitar. During rehearsals, Tom DeLio listened to it and told us there should have been more silence.

JC: Too active. Well, if you think of time as a canvas, and if you recall your experience of modern art, you can see that a canvas really can be empty. Or it can have a stroke just in one corner.

TM: What was the germinal idea behind Branches?

JC: It was originally made as an eight minute piece called Child of Tree, and it was to accompany a dance by Merce Cunningham which was called Solo, in which he seemed to be a series of different animals. He entered the stage like some kind of lizard, upright though, and he became a bird, and then one of the cat family, and so on. So I thought if he was being animals, I would be plants!

LF: How were the plants wired?

JC: It was done better than I’ve ever heard it. It was done with what’s called a C-ducer, and I mentioned that to David Tudor, and he also has three such things. He’s worked before, to my knowledge, with transducers, but these are C-ducers. It’s a strip that can be of different lengths, and it works — David was explaining it to me this morning — with some kind of feedback arrangement, and it’s not a passive microphone. It has to be powered.

I had a project — well, I still have it — but I’m not sure that it will be implemented. It was to be in Ivrea, Italy, which is the city where the Olivetti Company is, near Torino in Italy, and they had asked me to do something for children. And I said I would like to amplify a park so that all the plants and trees become productive of sound for the children to explore. (laughs) I found a hilltop almost in the middle of the town where you were up above the city and in view of the Alps, and the sounds that came up to that hilltop, when you were silent, were absolutely beautiful. Sounds of traffic, of people, and of animals. And then it was going to be arranged so that in an automatic way, the amplification of the bushes and trees would be available to the children, and then would automatically cut off, so you would hear this silence. It was going to work like that — alternations of the amplification taking place and not taking place.

TM: Do you plan to go ahead with this work?

JC: Other places now have asked for it, and I don’t generally have the feeling that one place is better than another, but that place in Ivrea was so beautiful — and it would have been so beautiful — that I’m reluctant to do it anyplace else.

TM: What other projects are current of interest?

JC: I have just finished a piece for twenty harps, and I’m about to start a piece for organ, and I still work on the violin etudes — the Freeman Etudes — which correspond to the Etudes Australes, and when I finish them I plan to write a series of etudes for — I’m think I’m going to do it twice, one for recorder or recorders, and once for flute.

TM: Some of these works are very difficult.

JC: They are, yes, they’re very difficult.

TM: Did you have a virtuosic element in mind?

JC: Yes, and these are intentionally as difficult as I can make them, because I think that we’re now surrounded by very serious problems in the society, and that we tend to think that the situation is hopeless and that it’s just impossible to do something that will make everything turn out properly. (laughs) So I think that this music, which is almost impossible, gives an instance of the practicality of the impossible.

LF: I remember Grete [Sultan] used to say, “I’m going to work on a few more measures.” She’d mark it off and work on a little section each day, really tiny ones, too.

JC: (laughs) Her devotion is absolutely extraordinary. I’ve known her for a long time, did she tell you? We had a common friend, another musician, Richard Buhlig. There’s a very great pianist now in Germany who plays my Music of Changes, and Grete played the first movement, and then it was because she was about to play the second movement that I wrote the Etudes Australes, because I didn’t want her to play the rest of it — because it starts hitting the piano with the fist and so on, and I thought that was inappropriate! (laughs) But this pianist is in Cologne, his name is Herbert Henck — do you know his name? I think he weighs less than a hundred pounds. When he comes on stage, he gives the impression of not being a regular human being, you know, and you think it would be better for him to go home (laughs) and rest or something! But then the moment he starts playing it’s as though the piece was on fire. Absolutely extraordinary.

LF: Has he been to this country?

JC: He must have, with his enormous energy. He also edits a very important magazine that brings out issues that thick, and very beautiful, on serious musical questions and situations. I think the magazine is called Neuland, new land. And Herbert Henck is his name. He’s married to another pianist who comes from Illinois. And just recently, when I was in Paris, a rather heavy, and tall, lady came up to me and said she was his sister! (laughs) He’s devoted to the music of Ives, too, and I think he got to playing my work through the enthusiasm of Hans Otte, do you know? He’s a composer and works at the Radio Bremen in Germany.

TM: Many composers tend to disassociate themselves with their earliest works. How to you reflect on your works of the ’30s and ’40s?

JC: I think of them as having their life, and I have mine. And I don’t wish them ill, you know. On the other hand, I’m not the person now who wrote them then, understand what I’m saying?

TM: There was a movement in the ’60s and early ’70s toward making process of composition audible within the music — in Come Out, I am sitting in a room, and so on. Has that every held interest for you — to make the compositional process audible in your work?

JC: I think it was Steve Reich who said it was clear I was involved in process, but it was a process the audience didn’t participate in because they couldn’t understand. I’m on the side of keeping things mysterious, and I have never enjoyed understanding things. If I understand something, I have no further use for it. So I try to make a music which I don’t understand and which will be difficult for other people to understand, too.

TM: Audiences, though, seem to have grown more perceptive and understanding toward your music.

JC: Oh, yes. I think that the first clear difference that I noticed was not between audiences and composers but between performers and composers. When Varèse’s Ionization was first played in the ’30s, it required seventy-five rehearsals. Then in the early ’50s in Illinois, young musicians coming from the farms and without any experience of modern music, really, were able to play Ionization better than it had been played in the ’30s with two rehearsals. It was clear then that something had changed. What was in the way of the people who needed seventy-five rehearsals was their experience. Satie said, “Experience is a form of paralysis,” and people, through their experience, become unable to do something with which they’re unfamiliar.

TM: To what extent have you been interested in computer music?

JC: Well, I did HPSCHD with Lejaren Hiller. I haven’t done anything since. I use the I Ching not by tossing coins but by a printout from a computer program, but that’s my only present connection with it, though I do think my compositional methods must resemble computer programming.

LF: What about the operatic medium? Does that interest you?

JC: I haven’t done that yet. I was going to write an opera, but that was in the late ’40s. And I had my libretto … I didn’t have the libretto but I had what it was going to be. It was going to be the life of Milarepa, which divides itself beautifully into three acts. But someone borrowed the book and didn’t return it, and it’s just through that circumstance I didn’t do it. It was difficult at the time to get that book, and now it’s easy. But I no longer have the feeling to do it. My sense of theatre, or my sense of that kind of work, is now changed to a work like Song Books or Theatre Piece.

TM: We understand you have enough material for a new book. Are you planning to release that soon?

JC: Yes. I think this next month, December, I will send it to the press. There are two more Writings Through Finnegans Wake, the fourth and fifth. In the Wesleyan book I’m not going to publish the third writing. It will be published either at Station Hill Press or somewhere else, but it’s a long one, so that that way all five will be available … the Station Hill Press plans to issue those five. Do you know their printing of Themes and Variations? That’s a book that they’ve published this year and done very beautifully, and an elaborate form of it is about to come out. The themes are fifteen different people who’ve been important to me in my work, life, and they’re not all musicians. They include Buckminster Fuller and Marshall McLuhan and Marcel Duchamp. In fact, I think the only musicians I’ve included in the fifteen are Satie, and David Tudor, and Arnold Schoenberg.

Preliminary to Themes and Variations, I did a good deal of write that is not in the book but was necessary in order to write what is in the book. And all that material is going to be presented in its handwritten form in facsimile showing all the errata and so forth, all the changes that went on. And it’s being done very beautifully. Then beside those two Writings Through Finnegans Wake there’s a text called James Joyce, Marcel Duchamp, and Erik Satie: An Alphabet. And then there’s the eighth installment of my Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse), and there are a number of other things. There’s a text in memory of a composer friend who died, and I was asked to write a text about him, and I did. And some other things. Those are the principal things, I think. The book will be called X.