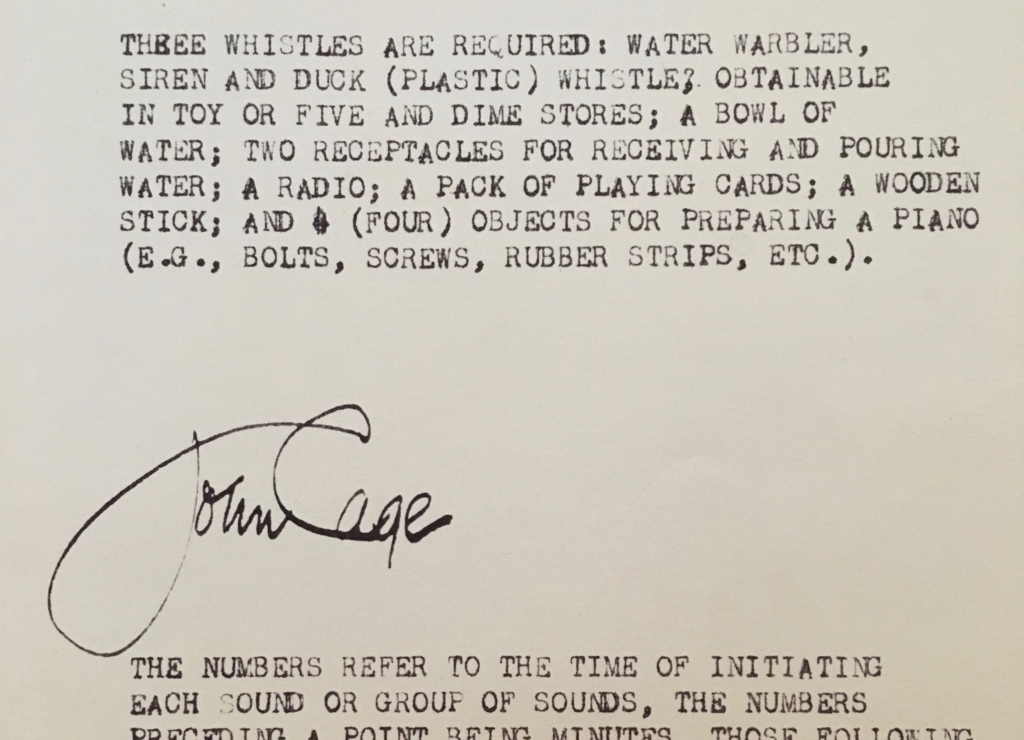

I first performed John Cage’s Water Music (1952) in November, 1988 at the University of Maryland, College Park, and it was quite problematic to prepare.

The score calls for a duck whistle, a water warbler, and a siren whistle. I assumed that the water warbler was a bird call. (By the way, Messiaen’s Catalogue d’oiseaux, which I was learning at the time, contains the sounds of nine varieties of warblers.)

My father-in-law loaned me what he thought was a duck call, but he wasn’t familiar with the water warbler. I looked up warbler in the encyclopedia, and it said that the warbler is primarily an Old World bird. I got worried. I remembered that in another piece Cage had made use of a cactus that could only be found in a specific region of Mexico.

My father-in-law suggested I call a hunting store in Gaithersburg, Maryland that would have lots of calls (ask for calls, not whistles). I called the store and asked about duck and water warbler calls. They had goose calls, and volunteered to loan me ten duck calls if I could return them after the performance. They hadn’t heard of a water warbler call. Why don’t you telephone the Audubon Society?

I called the Audubon Society number in Washington D.C. and explained that I needed to find a water warbler call. I was put on hold. Eventually someone answered and said that the office in Washington only did lobbying and that I had to call New York.

I called the New York number of the Audubon Society and spoke to a Mrs. Stevenson. She said that she had never heard of a water warbler, but that there were 30 other varieties of warblers in North America. Could I find out more about the bird? In the meantime, she would do some research for me.

I decided I’d better call John Cage. His assistant Laura Kuhn answered and said that John was away (Harvard lecture). I explained my problem and asked if she knew what a water warbler was. She said that she thought it was a plastic whistle, not a bird call, and suggested that I call Don Gillespie at C.F. Peters, who might know more about it.

I reached Don Gillespie in New York, and he said that, yes, it’s a plastic whistle that one fills with water. He said that he had found one in a Chinese store on Canal Street. He made me more worried than ever — I lived four hours from New York and had never heard of Canal Street.

When I hung up the phone it rang again. It was Mrs. Stevenson from the Audubon Society. She told me that the bird I was looking for was almost certainly the northern waterthrush, which was actually a member of the warbler family. I couldn’t bear to tell her that the water warbler wasn’t the northern waterthrush, it was a plastic whistle. Mrs. Stevenson proceeded to tell me a great deal about the northern waterthrush, including its markings, habitat, geographic distribution, call, and other information. I thanked her for letting me know.

I went to every toy, hobby, craft, and five-and-dime store I could think of. I couldn’t find a water warbler. Finally I talked to Tom DeLio in Washington, D.C. He said, call Stuart Smith — he has all sorts of things.

I called Stuart in Baltimore and asked him if he had a water warbler, and he said that he once did. He said to call Steve Weiss Percussion in Philadelphia. He said that Steve Weiss deals in odds and ends and that he would have one. I made a note to call in the morning (never did).

Later that night Linda Dusman called me from Worcester. I asked her if she knew what a water warbler was. She immediately told me the name of a toy store in Georgetown, D.C. (off Canal Street(!)) that sold water warblers and added that I should buy her one. While I was on the phone with her, I discovered that my father-in-law’s duck call wasn’t a duck call. It was a crow call. Linda said, you can’t use a crow call (crows don’t have anything to do with water).

The next morning I called the toy store. I was told that they didn’t carry water warblers anymore, but that they carried a plastic bird you could fill with water. “It makes a neat sound.” I was relieved. I told him to hold one for me. He said, I can’t, we’re out of stock.

I called every toy store in the yellow pages. None of them had water warblers; most of them had never heard of water warblers. One salesperson told me that water warblers are only around during the summer, and then only in specialty stores that handle imported toys.

I got off the phone. The music store called and said that two pieces by Christian Wolff had arrived. I said I’d be right over. I picked up the music and asked the clerk, Ed Hardy, if he had ever heard of a water warbler, explaining that it was a pipe that one pours water into. He said that, oh, no, that’s not a whistle, it’s a bird call, and he pulled out a large box of bird calls. He searched through the box and handed me a bird call that was labeled “Acme Nightingale Call.” He assured me it was really a water warbler (it is — this has been verified by water warbler experts), opened the package and showed me how to fill it with water. (Not only that, but they had a duck call, too.)

I printed in my program notes this story about finding a water warbler, and I sent a copy to Laura Kuhn and John Cage. About a week later a package from them arrived in the mail. A note from Laura inside said “We loved your notes.” The package contained a plastic yellow bird: a water warbler!

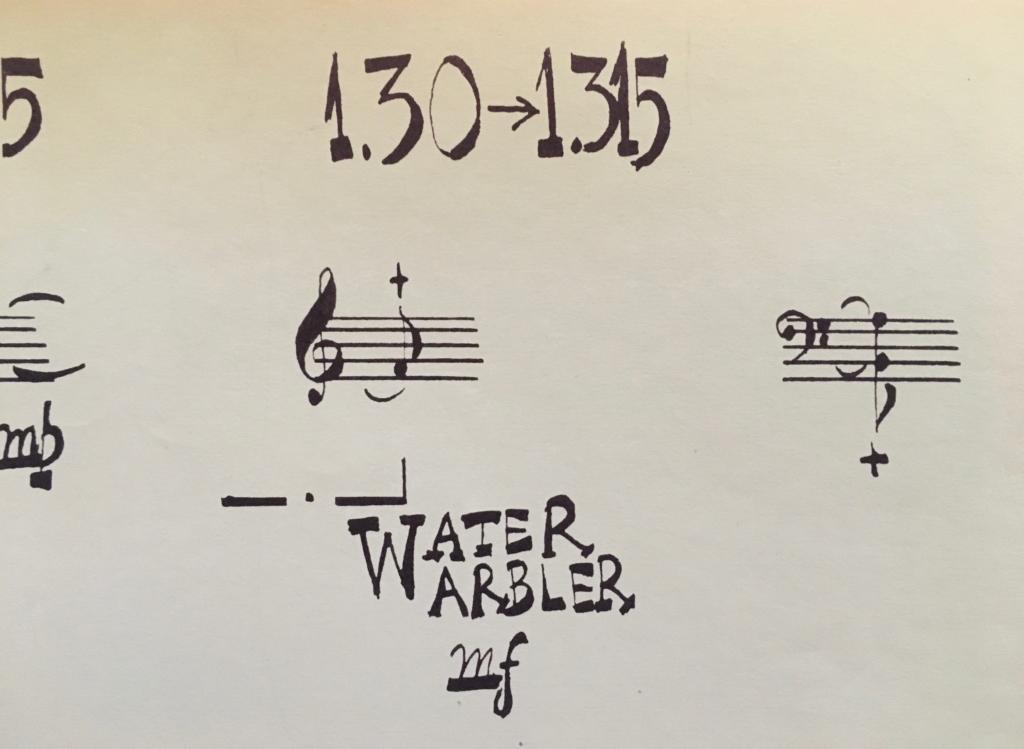

You can hear the water warbler for one-and-a-half seconds in Water Music, between one minute thirty seconds and one minute thirty-one and one-half seconds.

And — in the middle of all that insanity, I had overlooked that I had a duck call, and the piece called for a duck whistle. On hearing my performances, John said, keep using the duck call, it sounds better.